Doctor Henry Alfred Kissinger, the diplomatic heavyweight and pioneer of American foreign policy during the Cold War, died on Wednesday, 29 November, at the age of 100.

Kissinger was born in 1923 to a German-Jewish family in Bavaria but fled with his family in 1938 to escape the increasing risk of persecution under the Nazi regime. They ended up in New York City, where Kissinger completed high school and began an accounting degree at the City College of New York before he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1943. After basic training and education, Kissinger was assigned to the intelligence unit of the 84th Infantry Division, later leading a team that tracked down Gestapo officers and receiving the Bronze Star for his work. Upon return to the U.S., Kissinger completed his studies, obtaining a Bachelor of Arts with honors in Political Science, a Master of Arts, and a Doctor of Philosophy, all from Harvard.*

Kissinger’s work made him one of the main faces of American Cold War-era foreign policy, which his political career – spanning 60 years and the terms of 12 U.S Presidents – was largely centered around. A year after completing his formal education, Kissinger was recruited as a consultant to the National Security Council’s Operations Coordinating Board under the Eisenhower Administration, his first official affiliation with the federal government. In the 1960s, Kissinger assisted President Lyndon B. Johnson in communications with the North Vietnamese during the Vietnam War and also served as the foreign policy advisor for New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, supporting his Republican Primary campaigns in 1960, 1964, and 1968. During the 1968 general election campaign, through his work with the Johnson administration, he was notified of the President’s plans to broker a bombing ceasefire in Vietnam, later passing the information on to then-candidate Nixon – who had surpassed Rockefeller in the Primary Elections – showing the early signs of his political guile. The winner of the last of these campaigns was the 37th President, Richard Nixon, who appointed Kissinger as his National Security Advisor. In 1973, while still serving as National Security Advisor, Kissinger became Secretary of State, continuing in this role until 1977.

(From top to bottom, left to right: Henry Kissinger with Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden).

During Nixon’s presidency and amidst a turbulent era of global relations, Kissinger made the most significant and controversial decisions of his career. In March of 1969, less than two months into Nixon’s Presidential term, the Administration, in a continuation of operations that were initiated under Johnson’s Presidency, began a covert strategic bombing campaign in eastern Cambodia – an officially neutral state – as a response to the ongoing civil wars in both Cambodia and Vietnam, in an attempt to force the latter into a diplomatic settlement and stem the potential spread of communism from North Vietnam. Declassified transcripts of a telephone conversation in which Kissinger passed on information of the raids to his deputy quote him as saying, “He (Nixon) wants a massive bombing campaign in Cambodia. … It’s an order, it’s to be done. Anything that flies, on anything that moves. You got that?”. This conversation is seen by many as an indicator of the administration’s intent to carry out indiscriminate attacks on the Cambodian people.

Despite later claims of hesitation, Kissinger did not raise any substantial objections to the offensive at the time, and the attacks led to a complete strategic failure on the part of the United States: along with immediate casualties as a result of the bombings, lasting political consequences followed in Phnom Penh. A year after the first bomb was dropped, the Cambodian Head of State, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, was removed from power and exiled to China, ushering in the Khmer Republic led by pro-American Lon Nol. A period of domestic instability followed, during which time the U.S. assisted the Cambodian government in the deployment of half a million tons of bombs in the space of 7 months, killing as many as 300,000 people. The period culminated in the complete seizure of power by the country’s communist movement, the Khmer Rouge, a brutal dictatorship under the leadership of Pol Pot. The Khmer Rouge implemented an imitation of Mao Zedong’s infamous Great Leap Forward in China, which had taken place a decade and a half earlier. Under this societal reorganization, roughly 2 million citizens in the capital and other major cities were forcibly displaced into the countryside and made to pursue agricultural work, with thousands dying as an immediate result. This period later became known as the Cambodian Genocide, in which 1.5 to 3 million individuals lost their lives.

Simultaneously, Nixon and his administration began gradual troop withdrawals from Vietnam as the American presence entered its 4th year, pursuing a policy of ‘Vietnamization’, in which the U.S would provide sufficient support to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) while enabling them to handle the conflict against the pro-communist People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (Viet Cong) alone. The policy succeeded initially, allowing the U.S. to continue to withdraw troops, but proved insufficient in the long term as the bolstered ARVN still lacked the necessary munitions and strategy to counter the might of its opponents. The resulting Fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, was largely considered a humiliating event for the U.S. Kissinger, however, was able to derive positives from the conflict, as his prominent role in the negotiation of the Paris Peace Accords – an agreement between the U.S and the various Vietnamese parties to end the conflict and seek a peaceful resolution – led to him being jointly awarded the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize, alongside Le Duc Tho, a North Vietnamese diplomat who helped broker the agreements. While Kissinger readily welcomed the prize, Tho declined, saying that he would be “able to consider” accepting when the accord was respected, “the arms are silenced and real peace is established in South Vietnam”.

Another major element of the Cold War that dominated the Nixon Presidency was the country’s approach to dealing with both the Soviet Union (USSR) and China. At the beginning of the Nixon Administration, tensions between the United States’ two major geopolitical foes at the time were continually escalating, known as the Sino-Soviet Split. The U.S. sought to exploit this fissure through a policy of rapprochement with China, which Kissinger was instrumental in orchestrating. In July 1971, Kissinger made a secret trip to Beijing, meeting with Premier Zhou Enlai to discuss critical issues and discuss details of future relations between the two states. The following year, a quarter-century of separation between the countries ended as President Nixon visited China – the first sitting American head of state to do so – and met with various Chinese leaders, including Chairman Mao Zedong. The result of this trip was the reestablishment of diplomatic relations between the countries under the Carter Administration in 1979. Kissinger’s role in cooling tensions and restoring formalities with China is widely considered one of his most successful and longest-enduring career achievements, as the impact of his work over 50 years ago is still recognized today. Kissinger also occupied a significant role in the U.S. detente-era efforts in the USSR, which culminated with the Strategic Arms Limitations Talks & Treaty (SALT I), signed in 1972. These formalized relations continued in the following years and were punctuated by the summits in Moscow in 1972 & 1974, Washington in 1973, Vladivostok in 1974, and Helsinki in 1975.

Like its interventions in Vietnam and Cambodia under Kissinger’s foreign policy guidance show, the U.S. was committed to stopping the spread of socialism and communism in all corners of the globe to limit the USSR’s influence. Chile’s government was next to be forcefully restructured by the US. Its president, Salvador Allende, was democratically elected in 1970, making him the first avowed Marxist Head of State in Latin America. Allende aimed to implement a complete revamp of Chilean society and institutions, including the nationalization of the mining and banking systems, as well as the implementation & expansion of sprawling government programs. The U.S. had been wary of Allende long before his inauguration, viewing socialist control in Chile as a major threat to U.S. interests. In the 1964 election cycle, the Kennedy & Johnson Administrations channeled $2.6 million in funding into the campaign of Allende’s opponent, Eduardo Frei Montalvo, who ended up winning with 56% of the vote. Similar operations took place in 1970 when the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) continued to direct financial support to candidates opposing Allende. After his election, covert operations continued, culminating in a coup in 1973 led by General Augusto Pinochet, who ushered in a brutal dictatorship, under which over 40,000 individuals suffered detention, torture, and death at the hands of the government. Five days after Allende’s ouster, Kissinger told Nixon in a phone call that “we (the Administration) didn’t do it. I mean we helped them. (We) created the conditions as great as possible (sic)”, and that “in the Eisenhower period we would be heroes”. Shortly thereafter, Kissinger was appointed as Secretary of State.

Following Pinochet’s annexation of power, during Kissinger’s term as Secretary of State, the U.S. continued to support the Chilean regime, through the provision of military and financial support. These covert schemes were part of Operation Condor, a campaign orchestrated in the Cold War era and officially established in the mid-1970s, which provided U.S. support for authoritarian regimes in South America. These regimes “brutally and systematically repressed all forms of opposition”, including “members of leftist armed groups, political leaders, teachers, students, journalists, union leaders, and political and socialist activists”. The eight authoritarian governments the U.S. supported were responsible for “tens of thousands of people (…) were murdered or disappeared by military governments,” with an estimated death toll of 60-80,000, along with the capture of 400,000 political prisoners.

As Secretary of State, Kissinger also played a vital role in the United States’ Middle Eastern foreign policy, at a particularly unstable moment in the region. In October 1973, the Yom Kippur War took place between Israel and an alliance of Arab states, after an attack on the former on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur. Shortly before the conflict, when details of a planned attack by the Arab states were emerging, Kissinger urged the Israeli Prime Minister, Golda Meir, not to be responsible for a war in the Middle East and strongly advised against an Israeli strike. After the war broke out, Kissinger embarked on a mission known as ‘shuttle diplomacy’, a period in which he traveled back and forth between Egypt and Israel for a week, helping to negotiate a formal disengagement agreement between the two clashing states. Another Israeli-Egyptian accord followed, as well as a pact between the Jewish state and Syria; these settlements laid the foundation for the establishment of treaties between Israel and Arab states, most notably the Israel-Egypt peace agreement signed in 1979 as part of the Carter Administration’s Camp David Accords, as well as a variety of normalization agreements that were signed as part of the Abraham Accords.

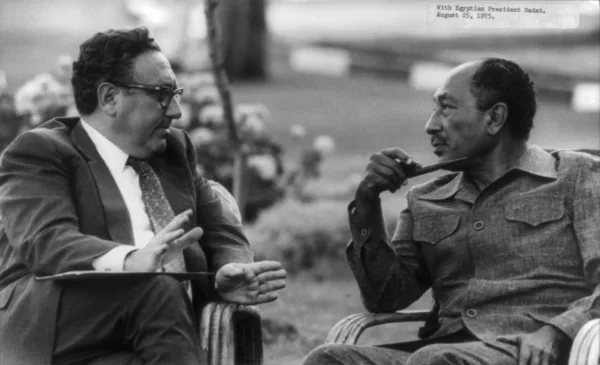

Kissinger’s use of ‘Shuttle Diplomacy’ during periods of Middle Eastern crisis has been highlighted as an example of Kissinger’s diplomatic wit and flexibility. Henry Kissinger with Golda Meir (left) and Anwar Saddat (right), heads of state of Israel and Egypt, respectively, during the Yom Kippur War of 1973.

Kissinger’s time as Secretary of State ended following the inauguration of Jimmy Carter in January 1977, but his affiliation with the federal government did not end there. In 1983, Kissinger was appointed by the Reagan Administration to head the National Bipartisan Commission on Central America, in order to “study the nature of United States interests in the Central American region and the threats now posed to those interests”. He was then selected in November 2002 by the George W. Bush Administration to lead the National Commission of Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, in the shadow of September 11. Kissinger, however, resigned as the commission’s head mere weeks after his appointment, citing conflict of interest concerns. Outside of governmental roles, Kissinger published a number of books, most notably his 3-part memoir series, which totalled nearly 4,000 pages, as well as the foreign policy-focused Diplomacy (1995) and On China (2011).

News of Kissinger’s death was met with mixed reactions around the world. Domestically, President Joe Biden praised Kissinger’s “fierce intellect and profound strategic focus”, with former President George W. Bush commending Kissinger’s role as “one of the most dependable and distinctive voices on foreign affairs.” Internationally, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin recognized Kissinger’s “sincere devotion and important contribution to China-US relations,” and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu lauded Kissinger’s “formidable intellect and diplomatic prowess.” Elsewhere, however, remembrances of Kissinger were less fond: Juan Gabriel Valdes, Chilean ambassador to the United States, referred to Kissinger as, “a man whose historical brilliance never managed to hide his deep moral misery”, with former Bolivian Ambassador to the United Nations, Sacha Llorenti, remarking that, “Plan Condor and the war imposed on the people of Vietnam are just two examples of Kissinger’s legacy”.

*Kissinger’s senior undergraduate thesis spanned 383 pages in total, forcing the University to implement its current limit on length for dissertations.