If you belong to Generation Z or a younger demographic, chances are you have been profoundly impacted by the forces of globalization and digitalization. This means your life has likely been characterized by mobility, multiculturalism, and you have gained a broadened perspective about the world. You have probably relocated several times, adapting to new environments and languages along the way. Whether through exchanges, studying abroad, or simply embracing different opportunities to be in the real world or in the digital space, your worldview has been shaped by diverse global experiences. Gone are the days when job searches were confined to local listings; instead, you’re empowered to explore opportunities across every continent. Unlike previous generations, who often remained tied to their birthplace due to familial obligations or travel restrictions, our horizons are virtually limitless.

Our grandparents and even parents have witnessed and experienced the constraints of geopolitical barriers, unable to even dream of traveling beyond the iron curtain, a term coined by Winston Churchill to describe the calamitous divide of Europe driven by competing ideologies, dictatorial regimes, and efforts to build a lasting framework for peace. This all took place while being the closest to nuclear self-destruction ever in human history, especially in 1962. It was a time of the harsh reality of a cold, polarized world anxious to turn hot: the era of the Cold War.

Reflecting on the past, it is striking to see how far we have come, and how deep we’ve sank after the passing of the unipolar moment – several short, almost fleeting years after the iron curtain fell, the Berlin Wall crumbled, and the world underwent seismic shifts that disrupted decades-long efforts of governmental control, ideological propaganda, and persecution.

In 1985, the song “Last Letter,” more commonly known as “Goodbye America,” by Nautilus Pompilius, a Soviet rock band of the ’80s and the ’90s sounded like one of the anthems of change, mirroring the zeitgeist of upheaval and newfound freedom in Soviet Union. It was the year Mikhail Gorbachev was elected as General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, who was determined to conduct a revolution from above, known today as the Perestroika. However, Gorbachev could not have anticipated the collapse not only of communism, but of the empire itself.

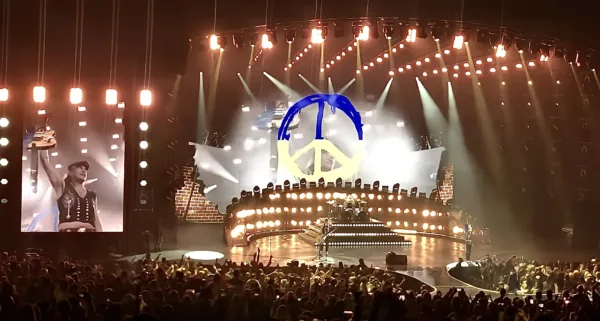

After nearly 20 years of economic stagnation under Leonid Berzhnev, people of the USSR were ready for change and to breathe in the air of freedom. That is why Vyacheslav Butusov sang: “Goodbye America, where I’ve never been, goodbye forever. Take your banjo, and play me one last time.” People no longer believed the propaganda of the West provided by Soviet information channels, nor did people live in a divided world on the brink of violence. At the dawn of democracy, people sounded the death knell for the Soviet Union with the establishment of independent republics with no foreseeable way to hinder the Union’s collapse. Then came the crumbling of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the Scorpions sang “Wind of Change” – a hymn signaling the changing world order and an era charged with new possibilities. So, like a prophecy, when on 25th of December, 1991, the flag of the Soviet Union was officially lowered one last time forever, the lyrics “I follow the Moskva and down to Gorky Park, listening to the wind of change” resonated in the hearts of people and transcended borders in promise of democracy, the expansion of liberal ideas, and the toppling of tyrannies in the aftermath of the Cold War.

Today, we know the promise was broken and our dreams were mercilessly betrayed. Since then, the Scorpions were forced to change the lyrics of the worldwide anthem to “Now listen to my heart. It says Ukrainia, waiting for the wind to change.” We are waiting, once again on the sidelines, to breathe in the wind of change. The song that once championed the end of the Cold War shifted in meaning when Russia invaded Ukraine, commencing yet another bloodshed on European soil, and we, the observers, were transported back in time to face yet another polarized world, this time promising to be more violent than the first.

As other nations like Myanmar, El Salvador, Ecuador, Ghana, Ukraine, Palestine, and many more find themselves embroiled in conflict and others like Brazil and Argentina find themselves democratically backsliding, it is evident that the winds of change are in transition. The optimism of Fukuyama’s “End of History” thesis stating that liberal democracy’s most important competitors: fascism and communism, have been defeated, and that there will no longer be any other ideology powerful enough to take on liberalism, has been vanquished by a sobering reality: the struggle for democracy and the rules-based international order is far from over.

Authoritarian regimes such as China and Russia persist and the technological revolution only assists them to further solidify their grip on power. They are eroding democratic principles like freedom of speech and electoral integrity through the exploitation of technology and increasingly fragmented digital social platforms. In the face of these facts, Fukuyama’s miscalculation becomes evident. While Fukuyama anticipated shifts in political dynamics, there are new movements on the rise that are challenging Western liberal values by using tools such as censorship of their domestic internet or implementation of firewalls limiting connection to the global web. Meanwhile, Western democracies struggle to prosecute malicious activity online such as the spread of harmful misinformation. What Fukuyama failed to predict was how the internet would fundamentally reshape societal norms and individual behaviors, and how those would undermine democracies around the world, since we have entered a period described by political scientists such as Larry Diamond as the “democratic recession.”

In the last few years, it has become reasonable to assume that the wave of democratization has ended, since many newly founded democratic institutions have started developing authoritarian traits such as the seizure of judicial power. This was seen in Nayib Bukele’s recent reelection as El Salvador’s president despite violating at least four constitutional articles overturned by the judicial court in 2021 with an aim to make Bukele eligible to run for president in 2024. This may seem democratic since Bukele won with an overwhelming margin of almost 83%, yet when considering the imposition of a state of emergency that suspended constitutional rights, allowed mass incarcerations, and dismantled systems of checks and balances, the democratic system in El Salvador is under threat. As such, Bukele’s government continues to usurp more power through constitutional amendments. Similarly, in other Latin American countries such as Bolivia, Brazil, and Guatemala, societies have faced stigmatization and repression of political opposition.

Europe is no exception to this trend, since nearly half of democracies in Europe have faced the erosion of democratic principles in the last five years as outlined in Global State of Democracy Report 2022. Some obvious examples are Hungary and Poland, where there have been democratic setbacks with the rise of populist regimes. Furthermore, despite the incorporation of laws on access to information based off of an internationally standardized version designed by the OAS general Assembly in 2010 – Model Law on Access to Information – countries in Europe such as Austria, Slovenia, Azerbaijan, and many more in other continents have seen a significant decline in Media Integrity. Meanwhile, autocratic regimes in Russia, Belarus, China, Vietnam, and Singapore have further consolidated in the last year such that it is almost impossible to recognize any democratic element present in their political systems. The reality of objectively competitive elections have completely vanished, and rights such as freedom of information, expression, press, and access to public information have been largely undermined. Such autocratic states rely on economic prosperity to legitimize their regimes. These developments are increasingly worrisome amidst international armed conflicts and the looming economic crisis.

Low quality information, disinformation that has gone viral are only some examples of dangers of a digitalized world exploited by authoritarian regimes. They undermine the bastions of democracy: the civil society and trust in judiciary institutions. Instead of allowing greater access to public information, many democratically elected governments chose to combat the spread of misinformation online through restrictive measures which further weaken civil societies and reinforce democratic erosion. As explained by UNESCO, “apparently, it has not been understood that, in the face of disinformation, the most effective antidote is greater access to public information. Rather, it has sought to combat the disinformation pandemic with proposals for legislation and restrictive measures.” It may not seem like it at first, but civil society plays an enormous role in protecting democracy and halting authoritarian advances through insisting on transparency and accountability. Only thanks to an active civil society was it possible for Indians to preserve religious freedom in spite of the Indian government’s attempt to limit it. However, civil societies across the world are consistently weakened by the internet, since instead of increased connectivity, social media platforms have promoted isolation and algorithms have encouraged individualization.

To recognize the internet’s dire impact on Western civil societies, it suffices to ask ourselves a few questions: Do you feel connected to your neighbors? Do you feel that you are actively engaging with your family members? Do you feel that you are developing meaningful friendships?

In 2000, Robert D. Putnam published his book titled, “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community” in which he explores the crucial role of civil society in sustaining democracy, particularly in emerging democracies such as post-communist countries. It should not come off as a surprise when I tell you that in the last two decades, we have signed fewer petitions, belonged to fewer societal organizations, and spent less time – or basically refrained from – getting to know our neighbors. We are meeting with friends less frequently and we dedicate less time to socializing with our families partly because of one button. Globalization and the emergence of digital spaces have created a false illusion that connection is only one button away. Internet companies and commercial and political advertisers gather information on our habits, interests, likes and dislikes creating a new reality where a code sometimes may know more about your life than you do. Businesses exploit your data for profit by using it to implement different forms of even more tailored customization.

Political identity itself has become a consumer good delivered by media companies, which in turn heightens popular dissatisfaction with the government since every single person only sees certain aspects of a political candidate they agree with, isolated in the bubble carefully constructed by data algorithms. Even when the dissatisfaction is justified, the lack of civic engagement due to the digitizing and continued materialization of our relationships leads to a decrease in cooperation and collective action as a society which is crucial in any democracy, consolidated or not. As Putnam explains in his analysis, “the quality of governance was determined by longstanding traditions of civic engagements or its absence. Voter turnout, newspaper readership, membership in choral societies and football clubs – these were the hallmarks of a successful region. In fact, historical analysis suggested that these networks of organized reciprocity and civic solidarity, far from being an epiphenomenon of socioeconomic modernization, were a precondition for it.”

The question is: where has our civic solidarity disappeared to? One possible answer lies in the Internet. We are currently living in a pandemic of loneliness, announced by the World Health Organization who declared it a public health concern. Never before in human history have so many people felt as lonely as they do nowadays. People are incentivized to go on social media platforms to seek social connection – one of the pillars of human existence. Even though it requires less effort to engage in conversation online, it leads to more shallow interactions by mere clicks of a button. Loneliness is not determined by the number of followers on Instagram, or how many people comment on your post. What truly matters is the quality of our social connections. Paradoxically, we have access to more social contacts than ever before, yet the quality of these relationships has significantly diminished. As people feel more lonely, more of them turn to the Internet in search of connection, perpetuating the cycle by spending more time online without finding meaningful connections, and thus reinforcing the feeling of loneliness.

Loneliness is proactively killing our democracies. The Internet facilitates the targeted approach of tailoring political messaging to individual preferences and erodes the shared sense of purpose essential for a cohesive democracy. It threatens the core of modern democratic values, because it eliminates any reason for coming together around a shared purpose in societies with dwindling social trust and an increasing trend to personalize and digitalize every single aspect of our lives. Therefore, when political candidates are portrayed through personalized lenses online, the collective endeavor of democratic participation becomes fragmented, normalizing an “every man for himself” mentality. Instead of developing social networks that nurture a broadened sense of self and transform the “I” into the “We,” the focus on personal benefits prevails over the collective benefits, making citizens less inclined to collaborate on common goals, leading to the absence of civic engagement with politics. Pericles, an Athenian statesman of the 5th century BC, warned of how the lack of civic participation inevitably leads to democratic decay, “Just because you do not take an interest in politics doesn’t mean politics won’t take an interest in you.”

For democracy to persevere it is crucial to stop privatizing and instead collectivize our leisure time. Meaningful connections often emerge from sharing stories and experiences with those around us. However, with the invention of television, followed by the internet and social media, our communities, even though expanded in size, have grown shallower. This prompts the reflection on the potential impacts of emerging technologies like virtual reality glasses such as VisionPro designed by Apple, which will offer entertainment in total isolation. Will technological advancements drive a wedge between individual and collective interests? Will technology deepen societal divides, or will we learn to integrate it into our lives while fostering deep connections within our communities?

Moreover, the current global events make me wonder about the destiny of democracy itself. Are all democracies bound to collapse sooner or later? If so, is it because the democratic principle to pursue personal freedom contradicts the pursuit of the collective good? Is that why communist ideals of the common good are incompatible with democratic principles such as free elections and the existence of an opposition? However, what if the self-destruction of democracy is something good? If democracy’s self-destruction were to occur, it would pave the way for a new democratic order rooted in evolving social values. Although, in that case, what role do authoritarian regimes play in shaping human behavior amid such shifts?

To simply ponder these questions would take more than a lifetime.

To conclude this essay, I would like to add some salt to the way the questions about political structures have been shaped: maybe there is no ideal system, but rather only supreme values such as human rights which can be inferred through Kantian logic and ethics. Democracy is not inherently perfect, yet, to this day, it is the only functioning system capable of adaptive change. It is the only political system that is explicitly designed to confront challenges by embracing them rather than suppressing them with violence. Democracy evolves continuously, embodying the spirit of perpetual change – the defining element of human existence. Democracy will endure as long as there are people who will strive to tackle obstacles collectively. For if we stop communicating, connecting, and impacting each other through positive change, what essence of humanity will remain within us?

So as Scorpions sang: “Take me to the magic of the moment. On a glory night, where the children of tomorrow dream away – in the wind of change.”

Featured image: Deutsche Welle